Living in Mexico for five weeks was a whirlwind of excitement and new experiences. Since returning to the U.S. a week ago, I’ve had some time to reflect on my experiences and discoveries.

First, I’ve learned to adjust my expectations of academic research. As I wrote in an earlier post, very little academic research exists on sex education in Mexico, which presented an exciting and slightly daunting challenge. During my first days of work in the Bank of Mexico, we located a plethora of sources, including a set of Social Values Surveys the 1980s, which provided information on societal beliefs surrounding women, gender roles, and family planning practices. I erroneously grew accustomed to the success, expecting it to continue for the duration of my internship. Visiting the Lerdo Library during my second week helped to ground my expectations. There, I examined archived newspapers in search of coverage of sex education controversies during the 20th century. From previous research, we had a range of dates to use as a starting point in our search. My naive optimism soon waned after hours of examining newspapers in Spanish with little to no progress. While the experience was frustrating, it was vital to my developing a realistic understanding of academic research.

One of the most interesting aspects of working in the archives was discovering the origins of sex education in Mexico. The impetus behind state-implemented sex education was the eugenics movement during the 1930s, Mexico’s Progressive era. Mexican eugenicists sought to introduce a sex education program in public schools. However, the movement ultimately failed due to its highly controversial nature. Throughout the 20th century, these political efforts were largely centered in the federal capital and other urban areas. The archival materials documented the opinions and movements in urban Mexico, but only told part of the story. While I worked in the archives, I found myself asking, “What about the rest of the state? What about rural Mexico?” Traveling to Oaxaca helped to me to answer some of these questions. Located south of the capital, Oaxaca is one of the most culturally and historically significant states in Mexico, as well as one of the poorest. A large portion of the population is of indigenous ancestry and lives in rural areas, with limited access to education, health care and other social resources. How do people access information on sex education in the absence of social resources?

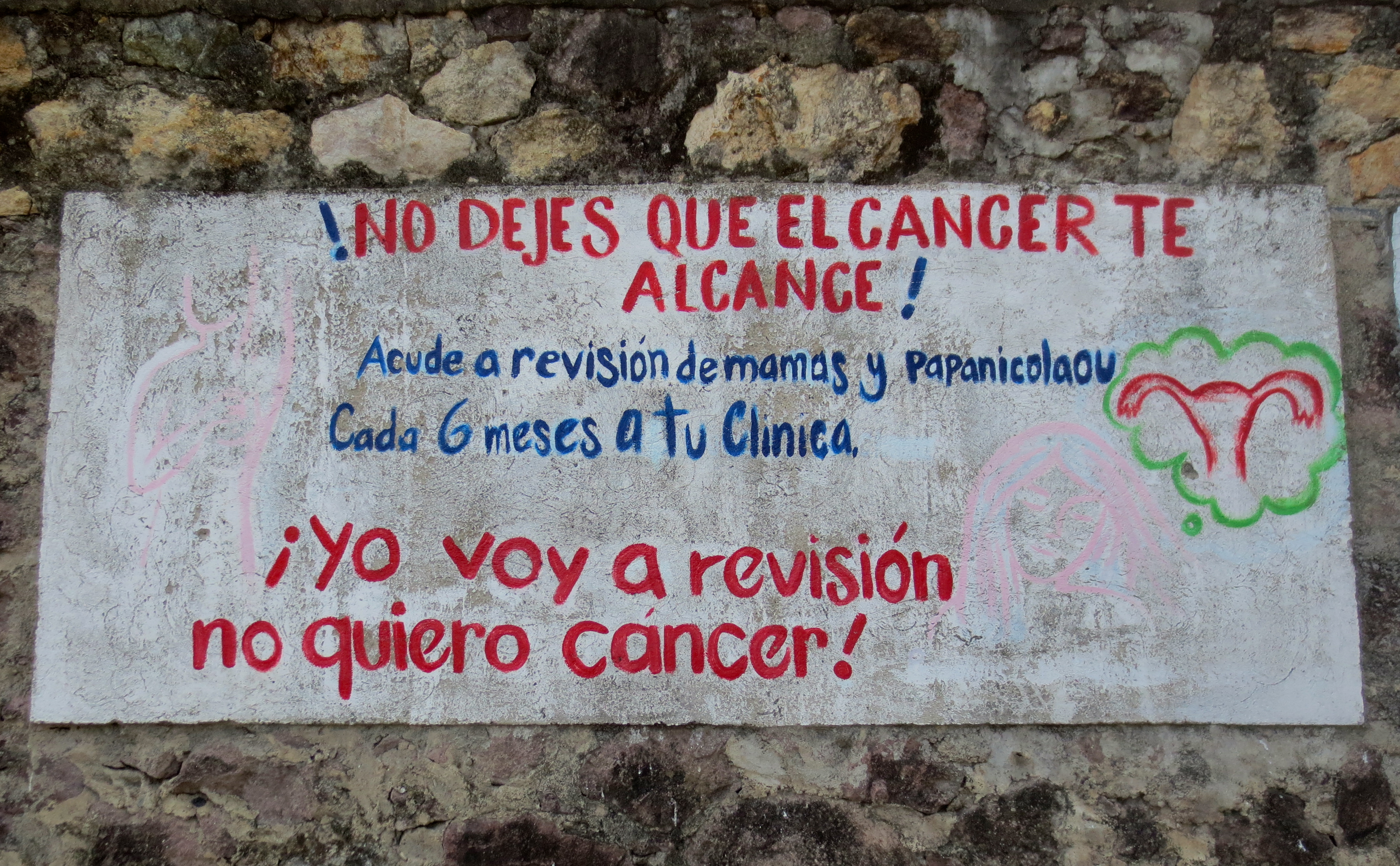

I realized that in order to answer this question I would need to look beyond the archives in unexpected places. One weekend, I traveled outside of Oaxaca City to hike the Sierra Norte Mountains. The mountain range is home to a number of small villages known as los Pueblos Mancomunados. While walking through San Miguel Amatlan, I noticed a wall full of murals. Upon closer inspection, I saw that the murals contained important public health messages, ranging from heart disease to malaria to female preventative health care. If I had not stopped to look, I would have missed this fascinating example of art and pop culture functioning as an unofficial, non-state led from of sex education. Below I have included a photo of one of the murals below, which encourages women to regularly seek preventative care and examinations.

Do not allow the cancer to reach you!

Go to your clinic every six months for a breast exam and pap smear

All things considered, I found more material than I would have expected. Still, it is humbling to recognize that my understanding of sex education in Mexico remains incomplete and that much research remains to fill the gaps in this unwritten history.